Tom's sculpture blog

My thoughts on why stone carving feels good, the history of sculpture, current developments in the art form, museum visits and exhibitions.

Why carving feels good

I carve stone because it makes me happier and helps me manage stress. It’s no coincidence that I started during a PhD and re-started after a major family crisis. But why does carving feel good? It’s something I’ve thought about a lot. Here's what I reckon so far...

Most artists add to create. Carvers remove. If that doesn’t sound a big deal and you haven’t carved before, give it a try, and enjoy the strange journey your brain goes on.

Removing unwanted material from a piece of stone, wood or bone to reveal something within that previously only existed in your imagination, is a weird experience.

But for some reason, it’s so satisfying that humans have been doing it for at least 40,000 years. That’s when the earliest known sculptures in-the-round like the Venus of Hohle Fels started to be made.

I’m not counting scratches made on cave walls, which go much further back, because psychologically I think this behaviour has more in common with drawing and painting. Carving a 3D object that you can turn around in your hands or walk all the way around is different.

As I kid I used to love drawing. I’m less keen on it now. It frustrates me in a similar way to how writing frustrates me. But I’m significantly better at writing than drawing, and it pays my bills so I carry on typing.

Stone carving can be frustrating too, don’t get me wrong. If you accidentally break off a crucial piece of stone, that’s infuriating. Corrections are much easier to make in a drawing or in an article, than in a stone carving. And sometimes sculptures pose practical challenges which are hard to think through. But turning a sculpture, stepping back from it and walking around it usually does the trick and that feels great.

Some stone carvers say that the sculpture is already in the block and they just release it with their chisels. I don’t think of it that way because my sculptures evolve as I work, it isn’t just sitting in there fully formed waiting to spring out.

But the important thing is: removing unwanted stone to get to a form you have in your head is really rewarding.

It’s a bit like clearing out clutter from a house and standing back to admire a pleasing new combination of light, space, lines and shadows. But it’s more than that because from the chaos you’ve also given birth to something new and more interesting than a tidy room, whether that’s a person, a bird, a frog, a monster, a landscape, clouds or a totem.

Sculpture v Painting

People have argued for centuries about whether sculpture or painting are the greater art form. I think that’s a pretty silly argument – why choose? But one reason why I love making sculptures is that they have a physical presence which people can interact with in a way they can’t with 2D art.

Painters master ways to trick the eye into believing that something exists. Stone carvers can create clever effects, for instance, carving and polishing alabaster so it becomes translucent. But they can’t trick viewers as a painter can. Some might see that as a limitation for sculpture but I value stone’s hefty truthfulness.

When you make an octopus out of stone, you haven’t made an illusion of an octopus, you’ve made an actual stone octopus which now exists in three dimensions in the world. If it didn’t exist, it wouldn’t be so heavy to pick up, it wouldn’t take up space in a room and a blind person wouldn’t be able to touch it and tell you what it is.

This is partly why humans love smashing up statues during revolutions. They are real so breaking off a stone nose, entire head or penis feels really satisfying. Scratching off paint from a canvas wouldn’t feel nearly so good.

Carving up a sweat

The physicality of carving is another part of its appeal. It gets me up on my feet, away from the dreaded laptop and using my body. Drawing, painting, printmaking and clay modelling won’t give you the same workout.

All art is good for combatting stress and lifting mood. I think carving achieves this in a unique way.

I can’t pretend it’s the easiest thing to ‘get into’. You need some tools and safety gear, some space, a suitable surface to work on and the right kind of stone. There are plenty of workshops around offering trial days or longer periods. Importantly many of these offer the chance to take something you’ve made home with you. But the other thing you need to make sculpture is TIME.

Slow down and chill out

I am very, very impatient and perhaps the greatest thing stone carving has taught me is “chill out, take your time, don’t rush, enjoy the moment and if it goes wrong, don’t worry, just calmly ponder and adapt.”

That’s the very opposite of what our crazy TikTok-accelerated world demands of us. And that’s why carving might just be the best thing you can do for your mind, body and soul.

Stony broke?

I think stone carving is in a weird period.

Many of the most financially successful stone carvers are making ostentatious but soulless garden ornaments, often relying on the wow factor of exotic multi-coloured stones.

Or they are making technically impressive but unimaginative Neoclassical statues in marble.

Some other sculptors make comforting figurative sculptures of animals, others imitate famous artists of the past like Barbara Hepworth.

Others are carving faithful copies of 21st-century objects (pill packets, trainers, phones etc). This might have been original and edgy for a while but now quite a few people are doing the same thing winning lots of Instagram likes.

Others (the ones I warm to more than the above) carve minimalist architectural pieces creating some delicious sharp lines and shadows.

I admire everyone who carves stone (it's a wonderfully mad thing to do) but I think it's fair to say that only a small minority are putting bold new ideas into stone in anything like the way that Jacob Epstein, for instance, was in the early 20th century.

Today, the most exciting sculptors emerging from art schools don't seem to be choosing to work with stone. They are opting for a range of other (more modern?) materials including metal, concrete, plastic and found objects. Great and good luck to them all.

But I love stone and I believe it remains relevant, powerful and versatile. That said, while I'm guided by the character of stone, it's still only a vehicle for my ideas. It may be physically hard and brittle but I try to bend it as far as possible to my will. Sometimes something (it or me) snaps in the process.

Lots of sculptors suggest the stone tells them what to carve or that the sculpture is already in the stone... they are just releasing it. I don't really get that.

But I feel strongly that sculpture should achieve more than showing off a naturally beautiful stone. Craftsmanship is important but ideas are equally important. Sculpture should say something.

I'm trying to start a conversation between past (always the historian) and present, and hopefully say something meaningful about our crazy modern lives and world. I have a particular interest in the themes of work, family relationships, climate change and technology.

Increasingly, I also want my sculpture to be visually challenging, to surprise viewers with unusual forms, beautiful ugliness, asymmetry, and the clash of roughly worked and highly polished surfaces.

Most importantly, I vow never to drill a hole though a minimalist abstract shape. I think that's been done already.

Two very different stone carvers I admire most today are Johnny Sunter and Lucy Churchill. Do check out their work.

Cypriot sculpture

In 2023, I visited a Fitzwilliam Museum exhibition called Islanders: The making of the Mediterranean and wrote a feature about it for the Cambridge Uni website.

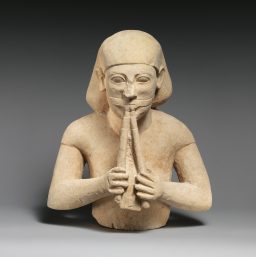

The exhibition exposed me to ancient Cypriot ceramic sculpture for the first time and it continues to blow my mind whenever I see it in museums.

The chap carrying the sheep shown here is one of my favourites. I love the style of these pieces but also how they capture moments of everyday life, industry and celebration.

These works of art were made before the Romans arrived and started spoiling things with their artistic rules. But even then, Cypriots continued doing things their way. Good on them.

There isn't much good carving stone on Cyprus but sculptors had plenty of clay to work with. Roman sculptures found on Cyprus were either made on the island with imported marble or shipped in already carved.

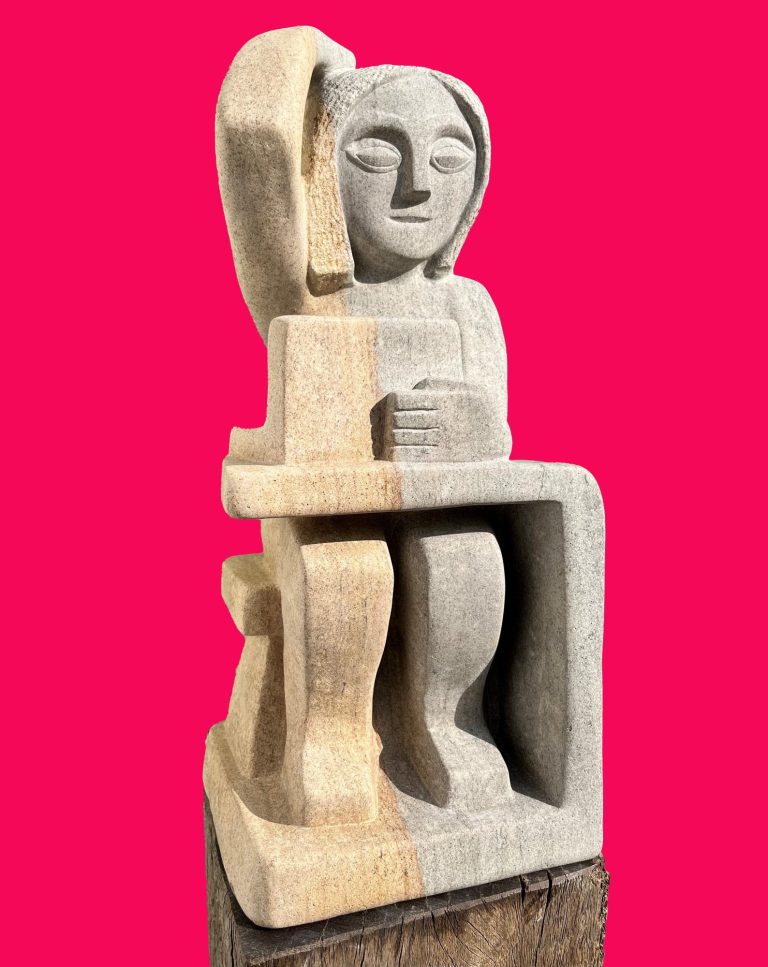

The Fitzwilliam's acclaimed Islanders exhibition featured some other incredible things, above all this limestone statuette made during the Middle Neolithic period (c. 5000 – 4500 bce) on Sardinia. I stared at this stone woman for a very long time and she stared back at me.

Read my story about the exhibition here.

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.